Psychological Safety#

One of the primary reasons we host hackweeks is to help build a culture of collaboration. We do this because research is becoming increasingly interdependent and because we know that cross-disciplinary exchanges increase the likelihood for us to address complex challenges. We also think that collaboration is fun and keeps our work more interesting and engaging!

In order for collaboration to occur we must be able to share information, ask questions and express our opinions openly [5]. When we ask these questions of people outside of our disciplinary boundary, we might be stepping into situations were we feel incompetent or intrusive. This is where creating a psychologically safe environment can help.

Psychological Safety: Defined

Psychological safety is a perception related to the consequences of taking interpersonal risks [4]. When people feel psychologically safe they can “express themselves physically, cognitively and emotionally” rather than disengage or “withdraw and defend their personal selves” [9].

In this lesson we will work on developing more insight into risk and all the ways it might show up in a short format training setting. We’ll do some exercises to assess our individual sense of risk and build our capacity to assess how others might be experiencing risk in a classroom, small group and 1x1 learning setting. Then we will share strategies for increasing psychological safety by highlighting the positive outcomes that can occur when we willingly take risks.

Note

Throughout this lesson we will be speaking about creating conditions for risk-taking in the context of interpersonal exchanges in a learning setting. It is important to separate this from other forms of risk that might impact people’s physical or emotional wellbeing. We will never advocate for risks that bring about harm to others. For more information please visit our Code of Conduct.

Hackweeks: a high risk environment?#

Let’s begin by thinking about the factors that influence our perception of risk at one of our events. Over the years we as organizers have often noticed participants feeling anxious and wondering if they belong at a hackweek. In some ways this is understandable! Here are some reasons why:

Hackweeks are a relatively new modality of learning and participants are often not sure what they are signing up for.

Hackweeks actively promote networking with people you haven’t met before, which might cause a sense of anxiety for some.

The short duration of hackweeks may cause many participants to feel a sense of urgency to get a lot done in the time provided. People might also feel they need to make the most of the money they invested in attending the event in person.

Hackweeks require participants to make quick decisions about tutorials they attend and projects they join, often with limited time for deliberation.

Hackweeks bring together novices and experts from across disciplines and career stages. It can be easy to for participants to notice where they are novices and harder to notice where they are experts.

To bring home this point, it is instructive to compare hackweeks with other forms of learning. When we sign up for a course in a formal higher education setting, we can look at a detailed curriculum, talk with past students, and find online reviews of professors. If the class isn’t what we expected, we can drop out after a few classes. Or, if we decide to learn through online resources, we can work at our own pace, and pick and choose content to our liking. All of these factors allow learners to minimize and mitigate risk in ways that might not be possible within a hackweek setting.

Lowering the stakes#

There are several ways we as organizers can work to reduce or eliminate some risks for participants. Some examples include:

Providing more information in advance of an event about course content and project ideas.

Designing icebreakers and networking activities in ways that attend to a diversity of personality types and ways of seeing the world.

Raising more funding to provide scholarship support and mitigate financial risks.

There are also some risks that we cannot control and might not want to eliminate. As a participant-driven learning model, some uncertainty and risk is going to be built-in to the hackweek experience. We believe the key to creating psychologically safe learning environments is to build our awareness of the stakes or consequences associated with each risk. If our assessment is that the stakes are low, then we can voluntarily step into risk without fear.

Note

Lowering stakes to create a sense of psychological safety is not the same as “lowering standards”. We are aware that there are many high-risk environments where the stakes are also very high. An example would be a surgeon performing a risky procedure on a patient. That would not be a time when we want to foster a “safe-to-fail” environment!

Risk, Power and Identity#

So far we have explored the risks inherent in the structure and design of a hackweek. Now we turn to the ways in which individual perception and experience of risk can vary with our personal identities. To explore these ideas we will use a framework that links together the concepts of power, privilege and interesectionality [10].

Let’s start with a few definitions. Each of us occupy a rich set of identities that may consciously or unconsciously impact how we experience and navigate the world. These identities include gender, sexual orientation, race, cultural background, ability, age, level of education, and numerous other factors. The concept of intersectionality [3] honors the fact that each of us has multiple, evolving identities whose interactions inform how we see and are seen in the world. For example, the intersection of our race and gender might create lesser or greater degrees of marginalization than either of these alone.

Privilege recognizes that some individuals gain advantages and benefits because of their identity. The concept of privilege challenges us to think beyond merit alone as a mechanism by which we gain advantage in society. People with greater privilege tend to hold more power, affording them the ability to influence and make decisions that impact others.

Oppression and marginalization occur when people lack power and agency and do not have access to resources and opportunities.

How do these ideas relate to the concept of psychological safety? If we occupy one or more identity groups that are or have been marginalized, we may be less inclined to step into risk. For example, people who have experienced marginalization in the past typically engage less in group discussions and are less likely to ask questions [7]. In contrast, those who are part of a more historically dominant identity group might be less concerned about taking risks because they have experienced fewer negative consequences for their behavior in the past. So, our willingness to step into risk, even if an environment has been set up to foster psychological safety, will very much depend on our intersecting identities and our related access to power and privilege.

Let’s try to make this a bit more concrete with an example!

Example: career stage

Academia has traditionally been organized around a set of hierarchical positions defining various phases of career stage and professional expertise. These institutional structures often create power dynamics that impact people’s learning experiences.

Over the years, we have noticed career stage playing an important role in how people relate to each other at hackweeks. Here are some examples of the inner dialogue we think might be occurring for hackweek attendees:

“I have a question, but I’m only a lowly graduate student and don’t want those professors knowing how little skill I actually have! I am going to find another graduate student to talk with first.”

“I came here to learn from the experts, so I am going to find a more senior person to talk to: they must have the most knowledge of anyone in this room!”

“I have been doing this work for 25 years, and I am a leader in my field, but I am completely lost! I don’t want anyone else to find me out so I will keep quiet for now.”

“This team I am in is all over the map! If this were my lab, I would be telling more people what to do.”

Questions for Reflection

How does my position in the academic hierarchy make me feel about myself?

What career stage are others at who are around me? How does this compare with my position?

Given our relative positions, what kind of dynamic do I think this sets up in the room?

Group Activity#

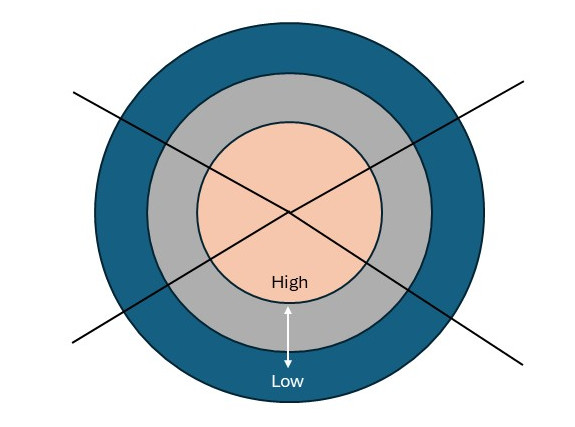

We invite you to reflect on your own identity and how this has shaped your experience so far in your career. Scholars typically use some type of circle or wheel to visualize intersecting identities and their interplay with power and privilege [11]. We’ll work with a version of such a wheel that locates high privilege in the center transitioning to lower privilege towards the outer edge of the circle.

Typically the center of such a circle is associated with greater power, and the outer edges associated with marginalization (see example wheel of power and privilege).

Activity Instructions

The purpose of this activity is to locate yourself on your own wheel of power and privilege. We will not ask you to share your wheel with others. Instead, we’ll invite you to reflect on how your levels of privilege might affect how you show up at the hackweek.

Choose 4 different identities that have particular meaning for you when you think about participating in a learning environment, and jot these down in a list.

Take the image we have provided of a circle. There are four black lines drawn on the circle. Write down your identities on these lines, with one word on each line. For example, you might write “gender” on one line and “career position” on another.

Now, draw a star on each of your identity lines showing where you place yourself on the continuum of privilege. The center of the circle represents a position of high privilege, and the outer ring represents low privilege.

Prompts for Discussion

What came up for you during this exercise?

What did you notice?

What insights did you have?

Suggested “hacks” to build awareness#

Here are some suggested things to ask ourselves when entering any learning space:

What dimension(s) of my identity feel particularly important for me to express or have awareness of in this space?

Do I know anything about the unique identities of others around me? What can I be doing to learn more?

How does my identity compare / contrast with others around me?

What are the opportunities and potential challenges of the assembly of identities in the room? What dynamics might need specific attention from me?

Are there any portions of my identity that afford me power? Can I use this power to help foster psychological safety for others?